Where are the People?

This is an edited transcript of my public lecture at TU Wien for easier reading.

Thank you very much for the introduction. Thank you for having me, thank you all for being here and coming back here this evening.

This is going to be a very different talk than the one I’m giving tomorrow. Tomorrow will be more the teaching lecture style, and tonight is going to be reflections on what it is that we’re doing as a field.

My lecture tonight is designed to be an invitation.

An invitation to think with me about information, about the role that information has in our lives as individuals, in our lives together as community and society.

To think about access.

Oh, wait, that’s the wrong access.

To think about access to this information and the process of people accessing it.

The technologies that we use, that we build, that we’re learning at the summer school this week to build to facilitate access to that information.

To think about why we are doing this in the first place.

Why do people need information? Why do we try to facilitate it?

What is our goal as we’re building a system, as we’re engaging with a system, as we’re thinking about the systems that should be built, the information artifacts that should be built, the repositories that should be built, etc.?

To think about what it means for information to be good, for information access and for an information access system to be good.

To think about how these systems can promote community, belonging, inclusion, equity, etc., both in the system and its use and its operation itself, and also how information systems and information access systems may contribute to or hinder those values in society at large.

I’ve been very pleased to see the pride flags proudly flying here in Vienna and signaling that inclusion, even as in my own country, many leaders are working to render queer people invisible in our public life.

How do we promote inclusion?

How do we promote the inclusion and the visibility of a diverse set, of the whole spectrum of humanity through our work on recommender systems and other information access systems?

So I’ve used this term information access a few times.

For those of you who might not be familiar with it, it’s kind of an umbrella term to capture a range of different systems that are facilitating people’s access to information: recommendations, search engines, and similar kinds of systems that let people find things.

We use them every day. We use them to find products that we want to purchase. We use them to find news stories that we want to read or that we don’t want to read, but they’re going to help us understand what’s going on, so we read them anyway. We find music, etc.

I think it would be very rare for most of us to go a day without interacting with at least one, if not a dozen, information access systems of various kinds.

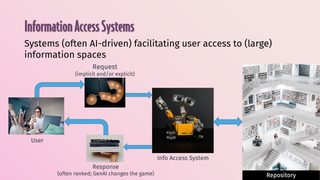

Let’s lightly formalize them as an object of study as we’re thinking about these systems. They’re a system, often AI-driven, but AI is not inherent to the process, and whether any individual system gets classified as AI has a lot more to do with the politics of research funding and venture funding than about the actual technology.

They are systems for which a user comes, with some kind of request. That request may be very specific: I want to know how to get from Vienna to Prague on Saturday. That request may be very vague: I’m bored so I open Netflix.

But the user comes with a request. That gets mixed up a little bit with mixed initiative things where the thing might actually proactively suggest, but we can abstract over that for a moment.

The system then takes that request, consults some repository of knowledge or information or something, and comes back with a response. Historically, these responses have often been ranked lists of products, of web pages, of books, of songs, etc.

Generative AI is changing that interaction modality a lot in many settings, but the basic loop persists. The user comes with some request and the system tries to satisfy it in some way.

These are the categories of systems that we’re talking about.

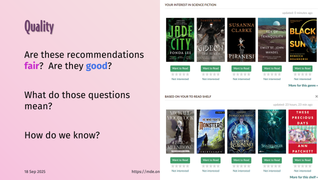

And so if we have one of these systems and it suggests some books for me, or I open Netflix and it says I should watch KPop Demon Hunters, is that a good recommendation?

Or if I type in a search query and the results are good, we can maybe ask other questions: are they diverse? What do we mean by that?

Are they fair? What does that mean?

A lot of my career of the last 5–10 years has been trying to figure out what it means to ask “is this a fair list?”. I have more questions about that than when I started, but I have a better idea of what the questions are.

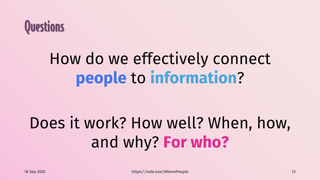

The broad question unifying a lot of my research agenda, and that I’m reflecting on with you tonight, is the question that drives a lot of information access research, whether it happens at RecSys or whether it happens at SIGIR or UMAP, o whether it’s happening in corporate research and development on building new products: how do we effectively connect people to information? With my researcher and my “trying to make the world a better place” hat on, I ask, does it work?

How well does it work? When? How? Why?

When does this system fail?

For who does it work or does it fail?

Who is getting harmed by the system, maybe unintentionally, maybe through neglect? In some cases, it may be deliberate.

And kind of the nagging question of, is what we’re doing as intersecting communities working on information access making the world better?

Are we delivering on some of the promise?

Are we causing harm?

How do we even know whether we’re improving things or causing harm?

And so in that context, for the set of things that I want to invite you to think about with me tonight, I want to start with why we even do information access.

As I’ve worked on a lot of these questions and a lot of these problems:

- What does it mean to be fair?

- In what contexts do we care about which types of fairness?

- When should we not try to be fair?

- Are there times when we should try to be unfair?

- What does it mean for the recommender system, the search engine, the chatbot to be good?

- In what sense?

- In what context?

I’ve it helpful to think clearly about what we’re trying to accomplish with the system, as designers, researchers, platform owners, what our vision and purpose for this system is. What the user is looking for when they come to the system, whcih might be different for different users.

And if you build a system, users will use it for all kinds of things you did not anticipate. There’s a story I heard a number of years ago in the social computing research community of this fascinating ad-hoc social network that had emerged among some residents in somewhere in rural UK in the comments section of a newspaper’s daily crossword. So the newspaper posted this daily crossword and then a bunch of people would show up in the comment section, they would have these discussions about life in their community and all these things. “We’re not gonna post on Facebook, we’re not gonna post on Twitter, we’re gonna post in the comment section of the newspaper’s daily crossword.”

So they’re going to use it for all kinds of different purposes.

But what are users coming to your system for?

Because purpose informs evaluation, and evaluation informs and guides design.

So everything flows downstream from why we’re building and operating the system in the first place.

The classic purpose that we think about that maybe we all learn to think about in our first information retrieval class, that’s kind of the baseline purpose assumed in a lot of research papers, is that we’re trying to satisfy some information need that the user has.

They come to the system, they have a need for some piece of information, and we want to satisfy it. This is very much the the default retrieval view.

As I said earlier, these needs can take many forms.

“Here we are now, entertain us” is an information need in my view. It’s underspecified, it’s very vague, it’s for entertainment-oriented information, but it’s an information need.

And the purpose of the system is to satisfy these needs.

And so then with that purpose in mind, we ask questions like, how well is it satisfying our users’ information needs? We’ll look for a bunch of metrics that we can compute with offline datasets, that we can compute by asking users whether their needs were met, that we can compute by looking at user behavior.

Does the way that they click on our results indicate that their needs are being met, etc.?

We can ask questions like, are all of our users having their needs met? Or is there a group of users who comes to our site and just isn’t able to find anything useful, etc.?

But this is one view of what the purpose of the system is. If you adopt this view, then you have a number of consequences in terms of evaluation, design, etc.

We can think about trying to promote economic opportunity and equity of economic opportunity.

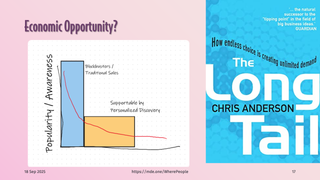

When I first started in recommender systems back in 2009, Chris Anderson had just published his book, The Long Tail. A lot of people were talking about it in the RecSys community. It was mentioned in several keynotes, etc.

This isn’t a full endorsement. The book has some weird parts.

But part of the fundamental logic of the book was with internet-scale discovery, internet-scale shopping abilities, global distribution capabilities, or nationwide at the very least, there’s an opportunity for a far larger set of products, creators, vendors, etc. to be visible, available, and viable.

The bottleneck of what the big box store or the shopping chain decides to purchase can be relaxed.

And a much longer tail of products — this is why it’s called the long tail — may become viable now.

But the key to making this a reality is personalization, and this is the reason that the recommender systems community latched on to this so much.

Connecting these niche musicians, these niche artisans, with the audience that will buy their product and allow them to have a commercially successful small-scale business, or even just a revenue-positive hobby, depends on being able to figure out which users and customers will resonate with their music, with their products, and which won’t. If we just randomly recommended people from the long tail, we’d recommend them to people who just didn’t get it and waste the opportunity, but there’s something else they would get.

If we want to unlock this segment of the economy, personalized information access is the key to doing so. Personalization on its own, if it is done well and effectively, can be an engine of economic opportunity by allowing larger and more diverse sets of people to find their audience and their customer base.

If we adopt this view, then we start to look at questions like “how is that opportunity distributed?”. Are we giving all the recommendation slots to the same ten musicians or are we getting a lot of providing opportunity to niche musicians? If a new author releases their first book, does it get recommended on Goodreads, or are the recommendations just full of the third fourth and fifth books by established authors?

A lot of questions flow downstream from saying this is the reason we’re trying to build the platform.

We may be thinking about information access in educational settings, either formal educational settings or informal ones, where our goal is to help people learn things to facilitate learning and knowledge acquisition.

We may be building a system that is intended to help users explore an information space or a product space and understand what different information is available and what information maybe they’re missing, or find and explore new musical genres or something.

If the goal is to facilitate this exploration and to facilitate this development of a kind of meta information — information and knowledge about the space of information — we might evaluate the system differently than if we’re only thinking about the system in terms of responding to individual fixed information needs.

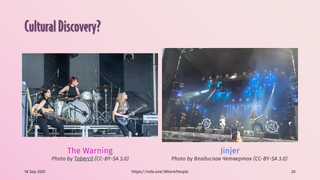

We might be trying to facilitate cultural discovery and cultural connection. The items, the products, the songs, the films that we’re recommending don’t just exist in a vacuum disconnected from humanity, but they’re created by people, in particular cultures, with particular goals and cultural backgrounds.

These are a couple of bands that I’ve discovered through recommendation in various ways, both through YouTube’s recommender, actually, because I like watching concert videos.

The first one [The Warning] is a power trio of sisters from Monterrey, Mexico, playing some of the freshest hard rock I’ve heard in a long time.

YouTube’s like, hey, you want to watch this?

I’m like, I’ve never heard this. Oh, sure, I’ll give it a shot.

Oh, wow, that’s good.

And they’re now doing very well. They’ve had some stuff go viral, and they’re touring internationally and things representing the Mexican rock scene to the world.

For that band, YouTube directly recommended their video to me.

The second, Jinjer, is a progressive metalcore band from Ukraine. This was an indirect recommendation — YouTube recommended to me not them, but a reactor who does song reactions. She did a reaction to a Jinjer video, and that’s how I learned about them. YouTube didn’t recommend Jinjer, but it recommended the person who recommended Jinjer.

And so now I listen to a fair amount of their music, and they’re also touring internationally and talking about the war against their country and representing Ukraine culturally on the international metal stage.

There is a human connection in these recommendations — the recommender system is connecting us to people and connecting us to cultures, either directly or indirectly, by making these kinds of connections.

We might think more generally about information access for connection. I just talked about artistic connection, but there are other forms of connection too.

There is direct connection: who-to-follow recommenders on social networks or dating recommenders, for example. They’re trying to very literally promote human connections

There is also knowledge connection where we’re connecting to other people through the recommendation of the material that’s describing their experiences. They’re writing blog posts, they’re writing LinkedIn posts, they’re sharing their knowledge and experience.

That’s being recommended, but through that recommendation, we’re also being connected to the person who produced it, to the person who is sharing this experience with us.

So human connection can be a goal of an information access system. And if this is your goal, then you might measure things related to human connection.

For one example, when Instagram rolled out their algorithmic feed ranker, they, in one of the blog posts, their research team or engineering team put out about it, they talked about how they measured, or they talked about measuring the probability that you’re going to see one of your close connections posts. Because if it’s just chronological, and your best friend posts a picture of their birthday cake, and you don’t log into Instagram for six hours later, and you don’t see it because it’s overwhelmed by everything else that’s been posted in the last six months.

And so with a goal of human connection, you can say, no, we want to promote that connection, and we know either because you’ve said it’s in the close friends list or just through looking at interaction density, we figure out this is a person you care about interacting with a lot.

When you sign in, we can say, oh, this close friend of yours posted their birthday cake six hours ago. We’re going to put that in the top two or three things rather than making you scroll to find it because you know you want to see your friend’s birthday cake.

And they measure that. They reported measurements of the algorithmic ranking really increasing the probability that if you posted something, your close friends would actually see it in the next hours or day or whatever.

But if this is your goal, you go try to measure it. You go try to design for it.

We connect people to each other individually or culturally; we can also think about connecting people to communities or connecting communities to each other or connecting people to communities of practice.

We can think about recommendation and information access to promote social cohesion. The people who are working on bridging algorithms are thinking about this: how do we recommend items that are going to cross divides and help people understand people who think very differently from them?

But the core to all of these is the people. That information access is a fundamentally human endeavor.

It’s for people, but it is also of people.

And thinking about these human goals provide guides for how we can design our systems, how we can design our valuations. They provide a framework for thinking about how do we do information access in a humanist kind of way, etc. They allow us then to think through what is it that we’re really trying to accomplish in the world?

Is it some abstract notion of some property engagement, perceived utility, fairness?

Or what are we trying to produce a more just and equitable society?

What’s the difference we want our work to make in our communities, our societies, and the world at large?

It also provides us a guide point to start to think about tricky situations.

What if someone provides harmful information?

Maybe it’s hateful. Maybe it’s misleading.

What if somebody wants that information?

How do we think through these kinds of questions and problems?

It’s not easy.

There are a lot of places we can start trying to think about these issues. I’m going to look at a few different lenses.

We’ll start by thinking about institutional ethics.

By institutional ethics, I mean codes of ethics that have been formalized and adopted by institutions, such as the Association for Computing Machinery, which sponsors the Recommender Systems Conference and many others.

One of the earliest points in their code of ethics is that computing professionals should contribute to society and human well-being. This is actually the first specific ethical principle after the preface: contribute to society and human well-being well.

That’s a goal that aligns with some of the goals that we’ve talked about. We can think about how we can do this through information access.

They also have one I skipped over, “avoid harm”, and this one: “be fair and take action not to discriminate”.

One of the very interesting things about this one that struck me when I read it is its proactivity. It doesn’t say just do your thing, and if you eventually learn that you’re discriminating, maybe do something about it.

It says to take action not to discriminate. To be proactive in anticipating how our own professional interactions and work may be discriminatory, or how our products and systems may be discriminatory, and to do something about it.

This is baked into the ACM’s Code of Ethics.

Since we’re thinking about information access, we might also go to libraries.

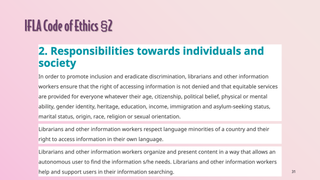

The International Federation of Library Associations also has a Code of Ethics for librarians and information professionals. They have a bunch of things in there.

A couple I’ll call out first is access to information.

And that’s the bedrock, the first ethical principle for librarians, information professionals: to facilitate people’s access to information without restriction, without censorship, and without discrimination.

Also that we have responsibilities towards both individuals and to society at large.

Here it also talks about to promote inclusion and eradicate discrimination.

And to do that, making sure that everybody has access to information that’s not being denied based on any personal factors.

It also specifically calls out respecting language minorities, not contributing to trying to erase languages, but providing people with information in their language to sustain language communities as well.

But we can also see very quickly in this code of ethics some political commitments.

This is not a neutral apolitical document.

They say that this first point, personal development, education, cultural enrichment, leisure, economic activity, and informed participation in an enhancement of democracy.

And it actually gives those as the reasons for facilitating access to information.

So if we adopt this code, if we want to live by this code, it calls specifically to the promotion of information access and facilitation of information access to support informed participation in democracy.

The preface specifically says that librarianship is, in its very essence, an ethical activity embodying a value-rich approach to professional work.

This also applies to computing. I sometimes hear in various contexts comments, like, well, I’m just building a system. Or it’s not my job. Or I’m not an ethicist or whatever.

But these codes of ethics and professional conduct for us as professionals or as professionals in training don’t say, oh yeah, you can just ignore ethics if you’re not trained in it.

This doesn’t mean all of us have to become professional ethicists, but we should take seriously the ethical responsibilities of our profession.

Choosing to go along with whatever is also a value judgment and a value decision. It’s not that, oh, we’re choosing to embrace values versus being value neutral.

It’s about what set of values are we embracing and are we living out and are we working out of?

As I noted, they’re specifically calling out promoting inclusion, eradicating discrimination. They’re specifically calling out informed participation in democracy. There’s a lot going on here in these codes of ethics.

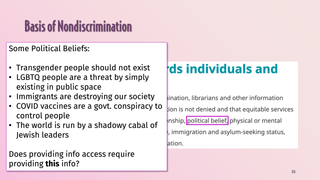

There’s also some complexity

Because the IFLA code talks about access to information regardless of political belief.

There’s a lot of political beliefs out there, some of which are very harmful to some groups of our society. How should we engage with that?

I will say the answer is not easy.

A lot of these things bring a lot more questions than answers.

Does providing information access require us to facilitate information, access to this kind of information?

That’s a question.

And it’s a question that regardless of how we decide on it, we shouldn’t just trivially dismiss. You can make a principled argument for yes or no, but make the argument and read the arguments.

If we engage with some of the reasons that are given such as promoting inclusion and eradicating discrimination, that might lead us to questions about whether providing access knowingly or unnecessarily facilitates showing people racist tweets about communities in their city, or does it promote inclusion or eradicate discrimination

It’s a question we should think about this paper engages directly with that question considering the quite the context of readers advisory librarians where people come and get suggestions for books to read and what happens with what the author calls oppressive tastes where someone like is specifically interested in for example violently misogynist literature so is thinking primarily in the fiction context what are the ethical obligations of the readers advisory librarian in that context and he grounds his response to that in this commitment to inclusion and this commitment to democracy in the library code of ethics that for step that material and unnecessarily providing that much like facilitating access to that material can create a prop problems for democratic self-governance and specifically it can distort our judgments of the credibility and pathic accessibility and fundamental worth of our fellow democratic citizens.

You also have questions of like, well, is it, who’s, is it librarians?

Not to say, no, you can’t.

But there’s also the question of saying, no, you can’t have this.

They probably won’t say that.

But like, no, I’m not going to help you find it is another thing.

Like, what is the balance?

I’m not going to say it’s easy.

And I’m not going to say we’re all going to land at the same place.

But I am going to say to think seriously about it.

So, that gets us to questions like if we’re thinking on, I raised earlier the question of okay, is everybody in our user group or are all the different groups of users of our system getting comparable access to information?

Well, is our goal to give everyone information that they perceive as satisfying their information need or is our goal to give them accurate information to the extent that we can assess that that aligns with their information need?

Again, not easy, but a question that we should take seriously and we should be clear with ourselves, with our colleagues, what it is that we’re trying to achieve with the system and then think about whether our evaluations are aligned with that, whether our designs are aligned with that, etc.

So I’m going to go quickly over this bit.

I have a lot of things that I can share with you, but I don’t want to keep you here all night and keep you from the beer.

So politics and even just democracy is not just one concept.

The political science literature recognizes multiple different types of democracy.

And we can actually see in the specific things that are called out in the Library Code of Ethics and the ACN Code of Ethics actually different emphases.

The library code of ethics reads to me as more aligned with participatory democracy or deliberative democracy as opposed to more of a classically liberal democracy that the ACM code more emphasizes in terms of economic opportunity and individual autonomy and things.

I’m not here to debate the relative merits of those two forms of democracy.

I think they both have a lot of merit, but even within, oh, we want to pursue democracy, we can be more specific.

For one example of this, there’s this paper that I really like by Sonny Bronhok and collaborators on looking at a bunch of different diversity metrics for news recommendation and thinking about which specific types of democracy do the different metrics align with.

Say, oh, if you want to support deliberative democracy, you might try to diversify your news in this way.

And that kind of very specific thinking about, because it doesn’t just have to stay at the abstract.

We can connect our specific goals to specific evaluation metrics, specific optimization objectives, specific design decisions in building an information access system.

And we should think about how to go about doing that if we’re going to build systems that affect the kind of change that we want to see in the world and that support the kind of society that we want to live in and that we want to contribute to.

So I’ll talk next a little bit about social connections.

So, as I mentioned earlier, if you set social connection as your goal, you can think about things like what kinds of things you optimize.

Are you just optimizing time on site, total minutes of video watched, total likes, or some other kind of direct engagement metric?

Or are you looking at other things, possibly not totally replacing those, but at least in addition to them?

Are you looking at the probability of a user seeing their close friend’s post within X hours of it coming out?

If you do, you can put that at least in your evaluation.

You might be able to find a clever way to put it into your system design.

Maybe you’re building a banded algorithm and you give a higher weight to the reward signal for something to come from someone’s close friend. so it learns to uprank things from close friends.

But you, so thinking about these goals, I think, like, we can sometimes think of ethics as maybe limiting, like, oh, what we shouldn’t do.

But for me, thinking about ethical principles, thinking about social goals like non-discrimination and debiasing, thinking about human goals for recommendation and information access, expand my vision of what it is that we can try to achieve through technology.

We can also think about recommendation itself as a community.

It’s maybe a little weird, but there’s this paper that I absolutely love from 1995, part of the very earliest cohort of modern recommender systems papers, that was specifically looking at using recommenders to kind of simulate community connection for information discovery.

And they had a few different design principles for a recommender system in there.

One was that it should ease and encourage rather than replace social processes.

They didn’t want the recommender system to replace talking with your friends or replace being a part of a community that likes some things.

They wanted to enhance that and maybe allow you to find community that you can’t find locally by connecting you to a broader national or global community.

They also argued that recommendations should be from people, and not in the personal, like, oh, I recommend this to you, although Goodreads has implemented that and people use it, but that it’s transparent, the system operating, These recommendations you are getting are based on consensus or behavior of this community or of other people in this community who are similar to you.

We can also think in terms of social connection of supporting expertise to the relationship of people and experts like teachers or librarians.

We have a paper in ACM Interactions a couple of years ago looking at actually four different models for how an expert like a teacher and a student can be involved together in an information access scenario.

Thinking about the specific scenario and designing to support that creates opportunity to think about how do we build systems that support experts rather than trying to replace them.

Because a lot of things are like, oh, we’re going to make this new AI thing and it’s going replace your librarian or it’s going to replace this or that expert in your life.

But if we instead there’s a broad design space to think about about how do we make those systems to help the expert more effectively help you not take them out of your life.

And this is where I want to talk about generative AI for a little bit because generative AI came on the scene.

It either changed everything or changed nothing depending on your perspective.

But I want to talk about a specific things it does change.

So I talked about a few different ways that recommender systems connect people to people.

And either directly or indirectly through like oh I’ve got some programming problem and it’s recommending me a Stack Overflow answer or a blog post or I’ll show my age a username article that was written by somebody who had that problem and figured out the solution and I’m like okay a fellow traveler dealing with this weird arcane thing of Python.

Also that person-to-person connection brings opportunity.

Economic opportunity whether it’s ad clicks or whether it’s subscription services or even just reputational opportunity.

The material is all free but oh a bunch of things I keep finding this person’s artwork and I need to commission an artist for illustrating this thing.

Maybe I’ll use them.

That kind of indirect effect.

When we just replace the recommendation of things created by people with generative responses, we are no longer connecting people to people.

We are connecting people to the system.

We’re no longer the middle connecting link.

We’re connecting it to the system.

And this is connected to what Cory Doctorow termed inshittification, which is sometimes simplified like things get worse.

But the actual theory of inshittification is much more subtle.

And his argument is that you build a platform built on connecting people to people. or people to vendors or whatever.

And then in the interest of profits and stock returns and those kinds of things, you look for where you can get more and more profit.

And you start to put on the squeeze.

Typically, you first start squeezing your vendors or suppliers and just making life progressively more difficult for them to taking a progressively larger share of their profits.

But they’re stuck because you’re their pipeline to their audience.

And then once they can’t squeeze them anymore, They start to directly squeeze the users, increasing subscription fees, more annoying ads, all kinds of things.

To finally just be capturing as much value to themselves as they can, rather than facilitating transaction and commerce between people and taking a modest cut to maintain operation and profitability.

That’s the theory of gentrification.

And saying, I’m not going to give attention to the bloggers, the news artists, the authors, etc.

I’m going to take all of the attention and opportunity to sell ads and all those things to myself as the platform.

That fundamentally alters the economics of information access and information production.

And it fundamentally alters the social contract around information and information access.

Because we kind of had this long-standing social contract of like, we’re going to let search engines index.

And they’re going to send us links.

And we’re not going to worry too much about like the finer points of the copyright.

There were some lawsuits and things, but kind of like there was this kind of status quo social contract that kind of emerged.

It breaks it.

That has consequences.

We’re no longer supporting connection and relationship.

We’re just, oh, we’re just going to give the generative response.

We’re no longer, well, the economic opportunity is fair because nobody’s getting any of it.

So they’re all getting the same if the system is just connecting the users to itself.

So, and then, like, this is also, it’s connected to the information retrieval folks have been talking for a while about, like, people aren’t looking for documents.

They’re looking for information.

Recommending that retrieving the document is just how we answer the question for information.

But, and now, okay, ChatGPT and other, Gemini and other LLM Power Chatbots, they’re actually delivering on that kind of a promise in a really big way.

Are we really prepared for the consequences of success in terms of its impact on communities, on human relationship, on the economics of information production?

why are people what’s the incentive for people to produce the information that GPT-6 or whatever is going to need to train if there’s no opportunity to get compensated for work producing information crucially so there’s a number of critiques of generative information access LLMs etc that are around the various aspects that they don’t work hallucinations those kinds of things crucially these critiques don’t depend on the not working in many ways their critiques about what is the world look like when they do work and it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t ever deploy an element anywhere but what we should do is think very clearly about what are our system goals.

What are our platform goals?

Does changing the modality in this way, we’re introducing that technology, advance those goals or hinder those goals?

If our goal, if we’re not in the business of connecting to people to people we might not care although not caring might have consequences down the road for us for our users etc.

But if we do uphold that value of connecting people to people that has consequences for how we think about the design of the system.

So I’m not saying don’t.

I mean I have a lot of skepticism but I’m not saying oh like oh just they’re the devil we need to throw them all away in every case.

I’m saying we need to think about our goal.

Why are we trying to facilitate?

What are we trying to facilitate when we facilitate access to information?

And what designs are going to advance that goal.

That’s my key, the key point I want you to take from this.

There’s also a lot of problems that are not working and promoting a lot of misinformation and things, but what concerns me a lot is that our information ecosystem and our societies in many ways feel to me like they’re kind of hanging on by a very fragile friend.

What are we doing as information professionals, as computing professionals, as professionals in training, to strengthen those things?

To build systems that promote healthy societies.

To build systems that promote robust and equitable marketplaces of information, of products, of art and culture, etc.

I would like to say a lot of things about power and control and the Pope, but I don’t have a lot of time left.

I will note, though, that there has been concern for a while among many, or among some at least, about the ability of systems to manipulate our individual and our communal perception of information, of the world of each other.

Belkin and Robertson talked about this back in 1976 in a paper that is criminally undersighted and underread.

The Pope also expressed concern about this in his message for the World Day of Peace in 2024 about the risk of AI systems manipulating manipulating people’s opinions and impressions and understandings.

We can design for more positive social spread things.

The notes and the slides and the bibliography will all be there for you to read at the end.

And so, to wrap up, where do we go?

I don’t want to just be talking about, yeah, so the purpose.

Thinking about what the purpose is is the big thing I want you to take away.

We all as individuals, as a community of practice on information access, recommender systems, etc., as members of our companies, of our other communities, have choices.

What we build, what we’re going to contribute to, what we’re going to use.

And so as we navigate those choices, we need to think about the purpose of the system, the purpose of our lives. we need to think about power and how it’s distributed and who has the power to make the system do this or that thinking about how we structure meaningful democratic accountability structures around technology so that power is not just held in the hands of platform owners and platform developers we need to think about the people who use the system who produce the information in the system who experience it and are impacted by it.

So with that, thank you.

And I’m happy to take questions. - Thank you, Michael.

So, Ms.. - Thank you so much, first of all.

I’m really passionate about that kind of topics and I always try to see or discuss with friends, especially I have a couple of friends from social/political science and it’s usually why I got into these topics, because we often, yeah, it’s a very fast researching, like the community, so many papers, so it’s a pressure to just develop and develop and not think, and then, yeah, we know we need to write in the papers about our motivations or purpose, but then you just, first you know the technique usually, and then you find justification, or that’s like, I feel like that’s most often how it happens.

I’m still a new PhD, but that’s what I feel.

And then, okay, one thing is like, yeah, if we are kind enough or ethical enough as researchers to think about it, that’s good, but we don’t have any other controls or something.

And what I have been thinking, like maybe on these conferences, even like Rex’s or whatever, we should have a track, I don’t know, I’m just also thinking about some tracks where actually political science people or social science people actually write papers about, like not technical people, but see what is impact for this or that method.

Like, yeah, so that there is something that makes us think about those things because we don’t know the literature, we don’t know the theories that they have, and we have logic to make these conclusions and think, but I still feel like it might still not be enough.

So what do you think about this? - I think it’s very important.

I think there’s a number of efforts that have been working in various directions on that, like the normalized workshop at Rexis on norms and values and recommender systems.

There’s also some, we’ve tried some with the FactRec workshop and responsible recommendation.

The Fact Conference is very much envisioned as an interdisciplinary place where some of those conversations can happen.

There are structural things that make it unnecessarily hard because computer science conferences have ridiculously high registration fees compared to social science conference registration fees and travel budgets.

And so it’s just, it is cost prohibitive often for a lot of people in social sciences and humanities, etc., to be able to come to computing venues.

So that’s a thing that we need to work on, is computing venues of either reducing those costs or finding ways to facilitate additional points of contact.

But I think, yes, that’s very important.

There are people who are working on it.

I don’t think we’ve made as much progress as we need to.

But, yes.

Yes, I have two questions.

The first one is, what would you recommend?

for us to do we are researchers i think most of us are concerned about ethics what would you do at a new workplace in your shoes to like actually pursue ethics in the world so i think i mean the first thing is is being aware of it and thinking about it thinking about like using it to guide which sets of problems do you choose to work on how do you frame those problems and that is as a challenge as she noted that a lot of times in our papers and the pressures of work etc of like we don’t bother to write in our motivation section like why we’re working on this recommender systems problem in the first place often or if we do it’s just kind of perfunctory and may not make any sense um taking that seriously even if it’s just like adding a paragraph in that’s like why you’re choosing this problem and why it matters with some citations.

That can be a starting point to think, and then think about like, think about then the connection of like, okay, so we should, we often don’t, but we should justify our choice of data set, choice of evaluation metric.

Tie that back to your purpose.

You’ve got that paragraph, half a paragraph that says, here’s why this problem matters.

And then your methods section, you’re talking about, here’s why these metrics are appropriate in the context of the problem I set out to solve in the first place.

And some of that is by example.

As we do that, I’m trying to do that more and more in my own papers, but as more of us do that, then that becomes the example that the next generation of students learns from.

And so some of it is just start, but you don’t have to solve all of the ethical problems in the world.

You can start by just being explicit with yourself and your collaborators, about what it is that you’re trying to do and reflecting that in your writing.

And the second question I had was more, this is very focused on what we as individuals can do, but do you think that as a community like the RACCIS community, either the conference or the research on the domain, should explicitly not just have guidelines or stuff like this, but a real political stance to refuse to just follow business objective, will also have explicitly political and ethical guidelines for our research?

Yes, but I don’t know that we should build them from scratch or on our own.

And I think some of it is not necessarily developing guidelines, but applying the ones that exist.

So we do need to be careful about just sitting and imposing our own values on others and when and how we do that.

But if a paper, if a research project is clearly in violation of the ACM Code of Ethics, should it be published in an ACM conference?

If you’re reviewing a paper that’s like clearly aimed at producing discrimination or clearly is, clearly and obviously is going to produce discrimination, my view is that you are, with appropriate citations, are well within the grounds of what should be happening peer review to say this project this system is clearly in violation of this and that principle the ACM code of ethics for these reasons so it should not be published at an ACM conference so some of it is applying the standards that already existed already been adopted by our communities or by our parent communities some of it is a starting point is is not necessarily imposing the standard of what should be done but opposing a standard of you have to talk about it so the NeurIPS impact statements are an example of this.

Rexis also had an impact statement in the submission process this year of you need to think about, talk about, reflect on the impact of your system, the consequences of your system, the ethics of your system and problem framing and then we can use that as a starting point to develop some of those community guidelines in a a way that’s informed by what the community is already thinking and already doing.

So I think, yes, we should be, as communities, thinking about what standards.

I think we should be conservative in codifying those standards, but we should be thinking about it, but starting with the expectation of talk about your system impacts.

Talk about why you’re solving this problem.

For one example of this, I didn’t actually put it in the bibliography, but I’ll add it to the bibliography on my webpage when we’re done here.

There’s a preprint that some of us have out, led by Alexandre Oltano of MSR Montreal, on rigor in artificial intelligence as its connection to responsible AI.

And one of the things we talk about in that paper is we call it normative rigor, which is being rigorous in justifying the AI problem you’re trying to solve.

Because a lot of times, and so basically our time in that paper is doing this thing where like, oh, we just solved the problem because that’s the data set.

We’re saying that’s not rigorous because you’re not rigorously justifying your choice of problem, your choice of data set, et cetera.

And so yes, I think we should be moving there, but starting with documentation and talking about it. - Thanks, thanks a lot for this. great talk, many important aspects and what I like also reflected from multiple perspectives.

I have a line of thought, just briefly, which might be provocative here.

And let me see when I come to a question.

Just a minute of my comment.

So when you started talking about, what is the name, information access?

I had something particular in mind on the web.

And then I was surprised that you didn’t mention it that good during your talk.

And also surprisingly, this thing I have in mind satisfies many of the aspects you have mentioned.

Possibility for exploration, informed participation, social cohesion, and so on.

And this thing I have in mind, when it’s a nice thing, I don’t need a recommender for that.

I don’t need a search engine.

I just need an internet browser.

This is Wikipedia.

So my question is, in Wikipedia, as I think, as I satisfy many of those things you have mentioned, my question would be– and I will have a question at the end of this comment– is this model something which works really only on this encyclopedic piece of information we want to access?

Or is this something we could now, having this experience of, say, the last 15 years in mind, is this something which could be extended to other areas of information access?

So I think it definitely can be extended to other information access areas.

And I think we see that in a variety of places, like the many other wiki communities that have come up, like communities that have produced exhaustive documentation of everything you can possibly find in any of the Fallout games.

I spend a bunch of, or like all these other kinds of things or ones that are built around artistic communities.

So like there is, I don’t remember where it is, but there is at least one extensive wiki on metal music where community documentation of metal subgenres artists that are doing different kinds of music within the genre.

And so when you have a passionate community that’s willing to contribute a bunch of free labor to their community, I think you can build really powerful information repositories that either are the access system themselves because you just browse or they facilitate that access. you could think about building a recommender on top of that metal encyclopedia that uses this human generated data about the relationship of the different styles and the different artists and things the power i like this band who are some others i should listen to kinds of experiences so i don’t think they’re mutually exclusive i think you can actually combine them together in very interesting ways as well.

I think figuring out how to develop and sustain the appropriate technical and importantly economic infrastructures to make that work and make that sustainable in the long term and make that so that it sustains maybe community-driven and community-owned information access instead of just serving as additional raw input for open AI to use to get richer.

I think that’s kind of one of the challenges that we have, but I think where we can make it work, yes, that’s a very, very powerful model that can apply beyond.

It’s harder to see it applying in some other, like it’s harder to see, say, how it might apply to a lot of e-commerce products.

But you could envision a style wiki that’s talking about clothing styles and clothing sustainability concerns and collecting a lot of resources about where and how to shop for clothes that look good or that kind of thing.

Reddit is also kind of a piece of that in some ways as well.

So any other questions, comments now?

I want to have the beer already.

Okay.

I don’t want to.

Sorry, Michael.

So one of the things that I worry a lot about with NAI is that we are taking it as gospel most of what comes out of it.

Taking about the things that are in generations and so on.

But often most people are uncertain whether they’re right, until they’re distracted with chat TVG or some other chatbot.

And there are ethical rules, there are morals, and so on that’s been set up.

But there is also a way of people describing things, indoctrination, kind of the underlying trend of the documents on the internet that is exploding in serious. that’s also kind of inherent inside of the I don’t know if you can call it the mentality of what is being answered in the models and I don’t understand how to evaluate it or how to be critical about it do you have any ideas or so I think there’s about five different questions in there I’ll try to take maybe one or two of them because I think there’s a lot of like there’s a lot of thorny, intertangled things.

There’s the thing about, there’s the aspect of how we as people relate to these systems and talk about them and think about them.

And that’s hard.

Like, people are gonna people.

I try to, like, we could try to use our influence and, like, explain to our friends, no, no, chat GPT doesn’t know things.

Checking with it is not, like, explain, like, you can try to explain what next token prediction means.

And pushing back on some things in some cases, I wound up being on an interview with one of our local public media channels talking about ChatGPT and had the opportunity to say, no, querying ChatGPT is not a thing.

This is not a query that you’re giving it.

It’s not a search engine.

It’s something different.

Talk a little bit about what that means.

But, like, where we have the opportunity, trying to correct some of those misconceptions, it’s not going to have as much effectiveness as we want.

But on the other hand, like, what can we do?

I think also, like, thinking about how we relate to them professionally and what we, through our professional activities, our professional communication, et cetera, are promoting, are legitimizing, et cetera, and what we aren’t. that’s also a very very indirect pathway to influence I think in terms of the things assessment of overall things like what does chat GPT understand about the web or as the about the world as reflected in the web and what biases are there what gaps are there how does that influence how we then try to use it for other things I don’t think any of us know it’s a fascinating research question that can produce many dissertations.

But I do think understanding train a transformer on a large and huge chunk of text, what does it actually learn about that, is a very interesting scientific question.

And when we set out to answer that question, I think we can get to some interesting places and we can then start to try to figure out, okay, so if I then try to use it to do this or that summarization, what am I actually doing?

What are the biases of that?

What is that measuring?

I think we just try to get closer but I don’t think any of us know yet but it’s an important question okay so the good news is that Mike will have a talk tomorrow and the first talk tomorrow will also be about ethics because Eric James is a philosopher and computer scientist so we’ll have a whole morning to go like into this direction and we’ll discuss and reflect on things so and I don’t know Michael will you come with us for a beer I hope?

Yes, planning to.

So thank you for coming, thank you. :::