To Serve Whom and How?

This is an edited transcript of my IR4U2 keynote talk for easier reading.

Thank you all for being here. Thank you to the organizers for having me here to talk with you about this question of who we’re trying to help with information retrieval, how, and really importantly, why.

I’ve subtitled the talk “Provocations” because I’m really hoping to start more conversations than provide answers.

We’re here at the IR4U2 workshop. At least I hope that’s what you’re looking for. The other workshops are down the hall.

But the question that I want to talk about today is why. And so we’ve got a relatively small group. Does anyone want to say why they’re interested in this problem of IR for understudied users?

audience supplies reasons

Thank you all. These are great reasons to be here.

What I want to talk about today is to get underneath some of these reasons. The “why” behind the why.

We want to ensure that our systems are more usable for people who don’t have access to them. More usable in context with low resource languages. Create resources to support information access for people who don’t have great access to it.

But underneath those is a layer of reasons. Why do we care about that family of problems in the first place? That’s what I want to talk about today. To talk about some various reasons that can be behind the reasons, even if we don’t articulate them explicitly, and particularly to discuss why those underlying reasons matter, and what consequences they might have for how we go about this work and how we resolve and think about some of the difficulties and challenges that arise in this work.

So really, not to tell you why you’re here, but to tell you why it matters why you’re here — that’s the big thing that I want to accomplish today. As I said, don’t expect to get answers from my talk today. I want to raise and start a lot more questions and provocations than provide conclusions. But I will have some candidate conclusions.

The really short summary is that I’ve come to believe as I’ve been wrestling through various problems in algorithmic fairness, that the reasons why we’re trying to pursue things like providing information access to understudied users, providing fair information access and all of the complexity and everything that that means, that the reasons why we’re doing it can provide really valuable guidance for navigating trade-offs, for wrestling moral complexities that arise, for understanding the limits of when this tool is not the right tool for the job.

And so I come to this to tell you a bit about how I got to this particular topic and the material I want to treat today. I spend a lot of time thinking about how AI in general, but particularly information access technology, can go horribly wrong and can cause or exacerbate harm. And there’s some discourse on AI harms and things that are like, oh, the Terminator is going to come and destroy us all. Terminator might come with an information need for clothes, boots, and a motorcycle.

But that’s not the set of problems that I’m most concerned with. I’m a lot more concerned with how the IR technologies that we’re building interact with the things that humans are doing and exacerbate harm that humans try to cause to each other or create new platforms and new avenues for that harm in some cases, or are providing benefits but are not providing those benefits equitably across all the various members of our society.

And so I’ve done a lot of work on this. It’s been the thing that’s consumed most of my attention for the last eight years. I’ve been doing other things too, but this has consumed a lot of my attention.

And I do see a significant connection between what we’re talking about here today and questions of fairness. I mean, all of us, we have a hammer, everything’s a nail, so we see things through our lens.

But when we’re thinking about trying to make information retrieval more useful, more effective for people for whom it is not currently effective, we are talking about a form of a consumer-side fairness problem of ensuring that the benefits, equity, et cetera, or the benefits, utility, et cetera, of information retrieval is available to everybody.

As a quick teaser, we’re going to be talking more about this in our paper in the IR for Good track on Thursday, for those of you who are still here, where we dive into a really broad view of the different consumer-side impacts of information retrieval, including usability and utility aspects and making sure those are distributed across various users.

My thinking partly comes from working in Boise State with Sole for seven years and seeing how we were approaching different sets of problems from different perspectives, but there also is this fundamental commonality of trying to ensure that IR systems are being good for everybody, being good for children, being good for various providers of the content, etc.

So there’s a unifying line of thought here.

But as I’ve been thinking through this and trying to work on and really get a solid theory of what am I trying to do with all this fairness research and work and why, and seeing how fairness discourse gets used and misused, a question arises: is the goal to make the information retrieval system fair?

Is the goal to make everyone able to access information retrieval systems?

Or is the goal something else? Is fairness a means to a further goal, such as promoting a well-informed society, or promoting equity of economic opportunity.

If we aren’t clear on means versus goals, then when the means runs into the limit and we’re treating it as a goal, we can wind up making some dodgy decisions.

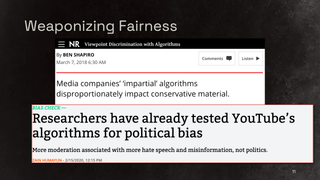

One of the specific challenges that I’ve been thinking about, and this is particularly happening in United States political discourse, but there are similar dynamics happening around the world. And so one of the things that happens in the U.S. tech political discourse is we have people complaining about that YouTube is discriminating against them or Google is discriminating against them, etc., by taking down their content or deranking it or things like that.

In some of those cases, they’re like, “I’m being discriminated against because of my political views.” And the counterargument is you’re just hitting the hate speech detector more often or the misinformation detector more often.

And so if you have, say, a political group that is significant, disproportionately producing more verifiable misinformation and hate speech, their stuff’s going to get taken down more frequently if the hate speech detector is doing its job.

So if we pursue “oh, we need to be fair on everybody’s own terms to every group”, we wind up asking “Okay, do we need to be fair to this?”

That might interfere with the broader societal goal of not having our information ecosystem just full of hate speech. Thinking about what the goal is versus what the means is helps us to start to think about it.

That’s the big thing that I want you to take away from today.

That example is on the provider side, people wanting to provide harmful information, but there’s also then on the consumer side. What if you have people, or coherent groups of people, who want harmful information and they believe that it’s true information? We’ll talk more about that in a little bit. But how do we start to wrestle with these? Where can we go?

I want to start by talking about institutionalized ethics as implemented in codes of ethics for various organizations, and look to those for perhaps a starting point on how we can start to think about this set of challenges and these sets of questions and how we can start to think about why we’re doing what we’re doing in this room here today.

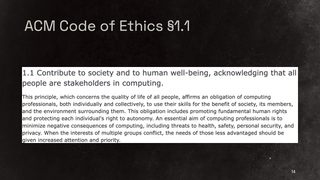

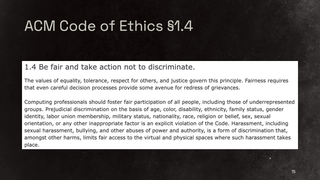

Let’s look at the ACM Code of Ethics for the Association of Computing Machinery.

Its first major bullet point is to contribute to society and human well-being and acknowledge that all people are stakeholders in computing. It then goes into detail about using skills as computing professionals for the benefit of society, for the benefit of people, for the benefit of the environment, promoting fundamental human rights, rights to autonomy, etc.

We go down a little bit further in the Code of Ethics and we see this point.

Be fair and take action not to discriminate.

Point 1.2 is to “avoid harm”, which is also really, really important. And I’m glad they put that before this. Like, oh, “our system is fair. It hurts everybody.” — we probably don’t want this.

But “be fair and take action not to discriminate”.

One of the things that I like about what the drafters of this code did is that this is proactive. It doesn’t say “don’t deliberately discriminate”. And it doesn’t say, “oh, go do your thing. And if someone, like, brings discrimination to your attention, do something about it.”.

It says “take action not to discriminate”. Be actively involved in the process of making our systems non-discriminatory.

And that connects with what we’re doing here today. If we’ve got a system that people can’t use, there’s good grounds to consider that discriminatory. If your search system has no accessibility, so it cannot be used by visually impaired readers who need to use a screen reader, your system is discriminatory against visually impaired users.

Already from this point, we can derive the need to work on IR for U2. Computing professionals should foster fair participation of all people, including underrepresented groups, avoid prejudicial discrimination on a long list of things. We have this kind of baked into computing codes of ethics.

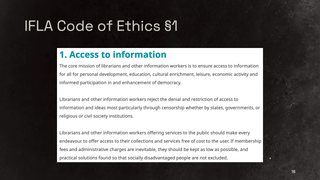

But this isn’t only in computing. The International Federation of Library Associations, which is the international group that various national library associations are affiliated with, has a code of ethics for librarians and other information professionals.

We’re here working on information retrieval. We are information professionals.

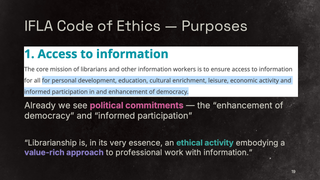

The IFLA’s first principle is to “ensure access to information for all”.

Librarians and information workers, information professionals, have a responsibility to work to ensure that everybody has access to information. And this is the first pillar of the IFLA code of ethics — it is foundational and core to librarian ethics.

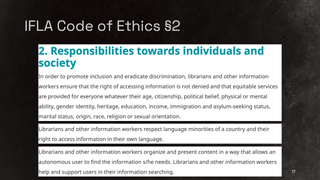

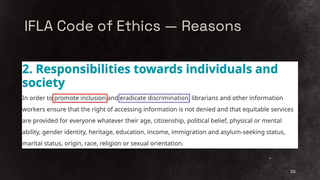

The second pillar, a section of the IFLA code, talks about responsibility towards individuals in society. It talks about the need to work to promote inclusion and eradicate discrimination. To do that, we need to ensure that the “right to access information is not denied” and “equitable services are provided for everyone”.

Whatever their age, whatever their physical or mental ability, etc.

And so it goes on at length about the need to make sure that information — and by extension, the systems that we build to facilitate and mediate access to that information — are able to be used by everyone.

It also talks about the need to provide people with access to information in their language. That library work and information work should be promoting and fostering the ability to access information in people’s own language, especially in language minority situations.

This effort can run up against significant forces that are trying to use linguistic homogeneity to remove cultures from visible participation in society.

There’s also an element of autonomy here. Librarians and other information workers organize and present content in a way that allows an autonomous user to find the information they need. And so it’s not just like, oh, I hand you the information, but systems that enable people to take ownership of their information access. Delivering systems and human interactions so that we’re enabling people to find information and to find the information that they need and that they want.

So we can see from all of these that we can’t – the work we’re doing here today, ensuring that everybody has fair – has effective access to information retrieval is essential to upholding and to carrying out these duties that have been laid out in these codes of ethics for various professional societies. And this includes long – like, children, language learners, neurodivergent users of various types, disabled users, etc.

And so making sure that – like, if we take these codes seriously, we have an ethical obligation to be doing this work.

But these codes, especially the IFLA code, go beyond just saying we need to do this.

They talk about purposes and reasons.

So the IFLA code says to ensure access to information for all for some purposes: for personal development, education, cultural enrichment, leisure. And informed participation in and enhancement of democracy.

This is not a value-neutral code, and this is not a politically neutral code. This code carries within it commitments to certain types of political orders, and the need for librarians to promote those types.

In the prologue to the IFLA code, it motivates the whole code with the claim that librarianship is in its very essence an “ethical activity embodying a value-rich approach”. So the whole code is premised on the idea that information work is not a value-neutral endeavor.

The code also supplies reasons. They say in responsibilities involving individuals and society, that these responsibilities regarding access are “to promote inclusion and eradicate discrimination”.

There’s a purpose to providing this access.

That purpose is heavily contested, at least in my country right now, where we have substantial arguments and forces arguing and working against inclusion. Working to retrench discrimination.

But the code of ethics includes this commitment.

So there’s a lot we can work with here in terms of thinking about why we’re doing IR4U2. Because I’m carrying out my duties under the IFLA code of ethics.

But there’s also some complexity that can start to arise from some of these.

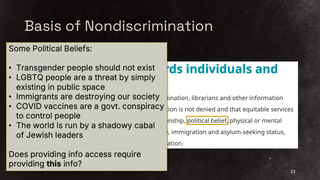

So these responsibilities — political belief as one of the things along which discrimination is not allowed. This winds up starting to get into some layers of complexity.

Here’s a bunch of political beliefs that are in live discussion in the United States and elsewhere.

How do we interact with these – with political beliefs? Particularly ones that are predicated on the harm and exclusion of others, or that are intended to support the harm and exclusion of others, when it comes to information access.

Does the need to provide fair information access entail providing access to information that reinforces political beliefs that are aimed at the exclusion and oppression of other people?

E.E. Lawrence took up this question in a paper in I think 2020 in the Journal of Documentation.

This paper looks at the question of what he called “oppressive tastes”. He was specifically looking at a service called Reader’s Advisory, but it applies to librarianship more broadly. In the U.S., Reader’s Advisory is a service where you go to the Reader’s Advisory librarian and at your library and you tell them what you’re looking for, you work with them to find books to read (particularly for fiction but not only). They’re a library service that helps people find things that they want to read.

Lawrence was concerned with the question of patrons coming with what he called oppressive taste. There’s at least a couple different versions of oppressive taste considered in this article. One is discriminatory taste in the form of e.g. a reader who only wants to read books written by men. Do you provide diverse reading suggestions to them?

Another is taste for oppressive content. For example, they want to read books that feature violent misogyny.

How does the responsible Reader’s Advisory librarian respond to these kinds of articulated information needs? Are Reader’s Advisory and other library services value neutral where the goal is to take the patron’s need or desire at face value and meet it? Or is there a different set of values in play where you say, yeah, I don’t care that you only want to read books by the majority ethnic group. We’re going to give you diverse reading suggestions anyway. Or maybe especially.

His conclusion is that, yes, librarians do need to engage in that value driven work to not just take those oppressive tastes at face value and reinforce them.

He grounds this in some things that we’ve already seen in the IFLA code: “on the view advanced here, oppressive tastes function as real obstacles to collective self governance”. They undermine democracy. Because they “systematically distort our judgments of the credibility, empathic accessibility, and fundamental worth of our democratic citizens”. He concluded that, yes, librarians should work to promote reading and promote material that encourages us to see our neighbors as valuable. To understand their experiences, their struggles, the oppression they’ve experienced as an input to our democratic process.

One way we can start to think about how this works out is where the IFLA code says “equitable services”.

But what is equitable? Is equitable service where all of the users get information that they subjectively perceive as satisfying their need? Regardless of whether that need is an oppressive taste? Regardless of whether that need is information that reinforces their belief that COVID was created by lizard people from space?

Or is it accurate information related to the user’s topical interest even if they do not perceive it as accurate?

Which of these is an equitable service? The code doesn’t say. But I would argue that this is where we can start to think more richly about how is what we’re doing engaging with the duties and responsibilities and the potential challenges.

I’ve got about five minutes left, so I will probably move quickly through a few of the points.

But basically, as we think about this, there’s complex questions in terms of who’s potentially being harmed, and it’s not necessarily the person in front of us. Like, the oppressive taste situation, the person who’s coming to the library, they might be harmed in the sense of reinforcing oppressive beliefs might be a harm. But also, they’re getting those reinforced as harm to their neighbors.

So let’s think about what our goal is. As Lawrence did, thinking about the goal of promoting understanding our neighbors as a part of the democratic process gives us guidance to think about how we want to navigate some of these challenges.

So, politics, briefly.

We can see also in these IFLA codes. As I said, the IFLA code is a value-rich proposition that is committed to a certain type of democratic order.

It’s democratic order, but a certain type of democratic order. They talk about things like informed participation and promote inclusion. This sounds a lot to me like pluralistic deliberative democracy.

The ACM code has a lot of similar things, but it has a different emphasis. It focuses on equality, tolerance, and respect, but it focuses a lot more on autonomy, and it has kind of more of an economic flavor to it. If we want to debate theories of democracy, it sounds like liberal democracy, but also both of them are heavily committed to pluralistic forms of those democracies.

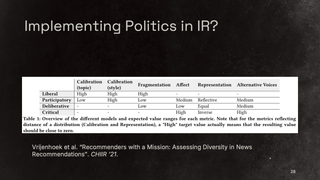

Really quick sidebar. I want to just let you know this paper exists because it’s fascinating.

So, Sanne Vrijenhoek and her collaborators did this piece where they looked at IR diversity metrics and how they map to specific theories of democracy. Liberal democracy, participatory, deliberative.

This is just to show you that thinking about what it is that we’re trying to achieve doesn’t only impact how we design the research or the kinds of applications we build. It can have direct impacts in what IR metrics we use because e.g. this one maps to deliberative democracy.

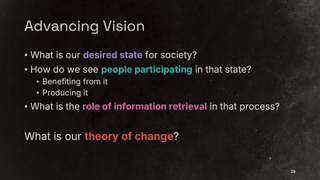

As we’re thinking about these goals, I think what’s really interesting and useful to think of is what is our desired state for society with regards to information or in general?

How do we see people participating in that state, either benefiting from that state or doing work that brings us to that state?

And then, what is the role for this room of information retrieval in that process?

When we put these together, we’re talking about what’s called a theory of change. Theory of change is a concept that comes from sociology. It also shows up in environmental research and things.

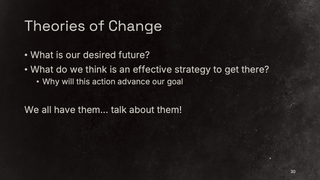

All of us have a theory of change. We just don’t necessarily talk about them. But a theory of change partly consists of what desired future we’re trying to work for — everyone can access information retrieval or the future that we want that to build to. And also, we’re taking specific actions in order to try to bring that world about. Why?

The theory of change gets us to why do we believe that this action is going to bring us closer to that desired end state? Different theories of change will lead to different actions to the same desired end state.

We all have them. But we need to explicitly articulate them and think about “why do I believe that doing this work is going to get me there?”

I also want to talk super, super briefly about what we are inviting people to when we’re involving information access. Because we tend to treat it as good. Hey, people get access to information retrieval.

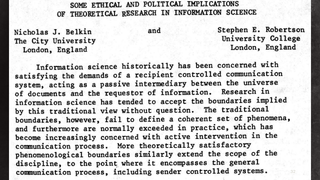

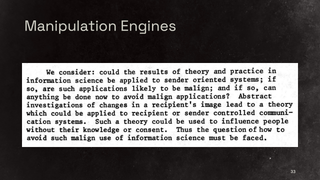

But this paper, a criminally undercited paper by Belkin and Robertson in 1976, they were concerned with the ability for findings in information science to be used against the users. The work we’re doing on how to facilitate people accessing information, how can that be misused particularly to what they called sender-oriented systems? Propaganda machines.

How can the theories that we build of how people access information be flipped around to build systems that push particular messages and shape the discourse of our society?

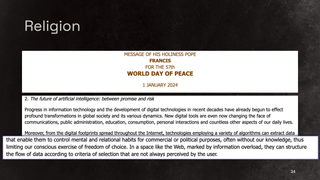

The Pope is also interested in this question. In a message for the World Day of Peace, Pope Francis wrote about AI in general and also said a number of things about search and recommendation in particular.

He talked about algorithms that enable platform providers to “influence mental and relational habits, often without our knowledge”. “In a space like the web marked by information overload, they can structure the flow of data according to criteria of selection that are not always perceived by the user”.

This is what Belkin and Robertson were talking about too. The ability to build systems that structure what we see and how we see it and how the data flows in ways that can have subtle and manipulative effects on society. So, there’s lots of reason to be concerned about this.

Then this gets to… We bring someone in, we give them better access to information retrieval.

Are we giving them better access to being manipulated by the structure and control of the flow of information? Now, it still may well be a better state than they had before, but that’s something to think about.

Information and resources, opportunity

Manipulation. Exploitation.

Are we making it easier for people to be grist for the surveillance capitalism machine?

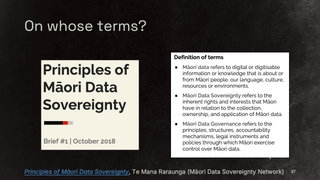

On whose terms are we doing this in a way that respects individual and community autonomy?

Are we doing it in a way that equitably distributes the benefits and the costs of information retrieval? This book talks a lot about that, not specifically about information retrieval.

And who gets to be involved in design of these things?

And are people being designed for or being designed with? This is one of the big challenges I would like to see information retrieval work on in the next five, ten years. How do we enable people to design the information retrieval systems they interact with, not just use the ones others have designed?

So what do we do with all of this?

Access to information, effective access to information, and expanding that effective access is really, really important. For ethical reasons, for political reasons, for economic reasons.

But there’s tensions that happen in this. There’s competing interests and harms. There’s questions of how power is allocated.

It’s important to be clear, I believe, about why we’re doing this work. And to let that why guide us.

[fin]