Notes on Probability

This document summarizes key concepts in probability theory. It is intended to be a concise reference for what I use in classes and research writing, not a thorough tutorial exposition.

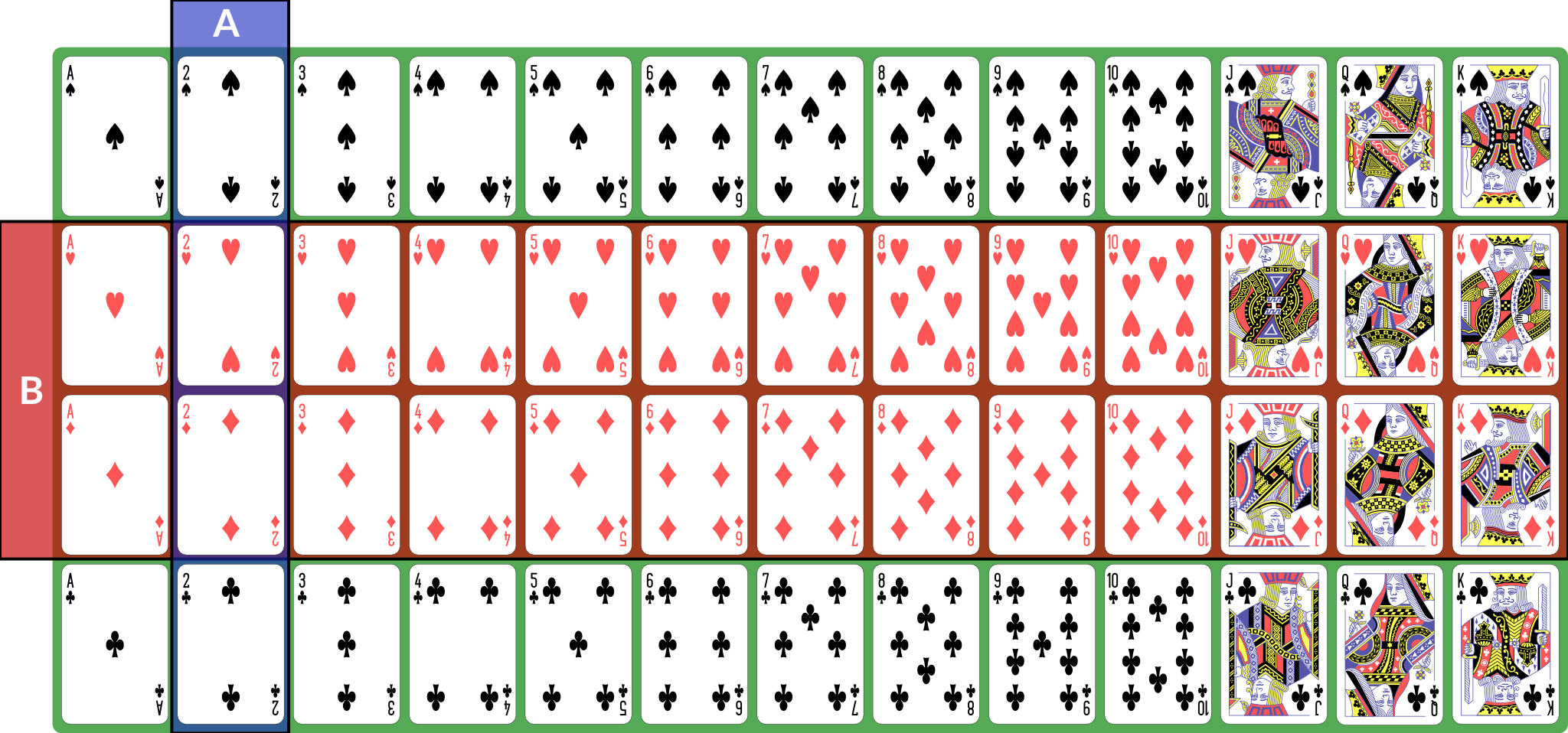

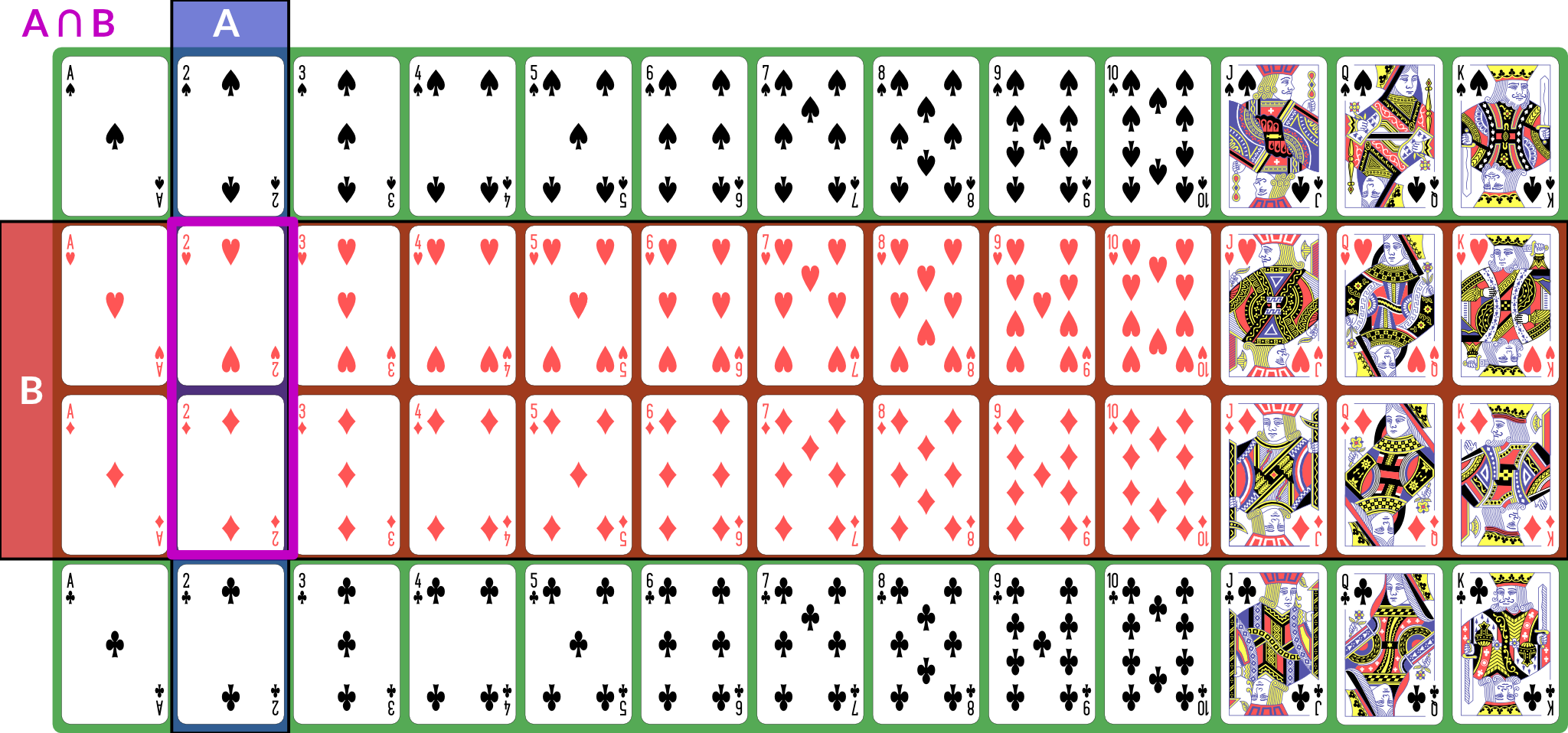

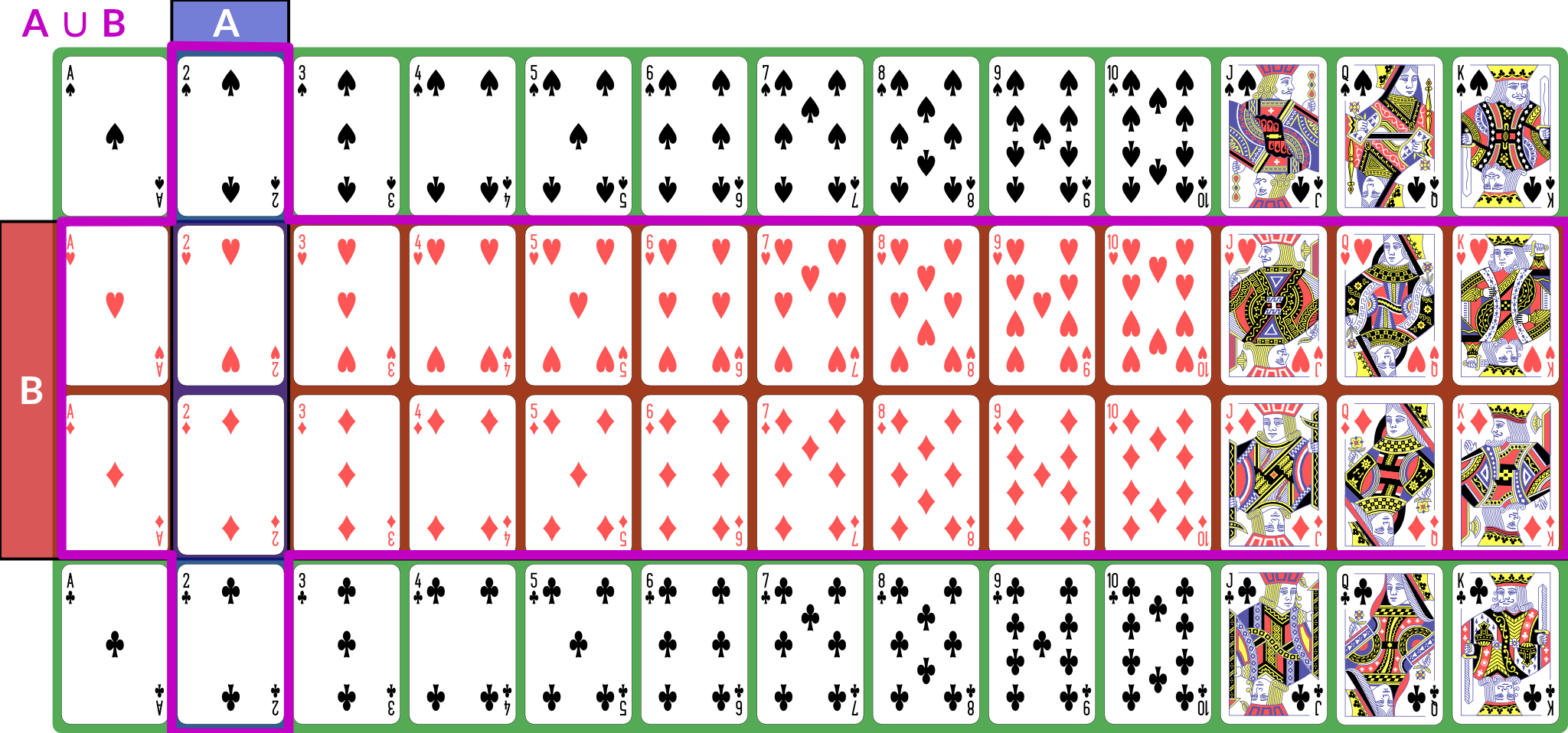

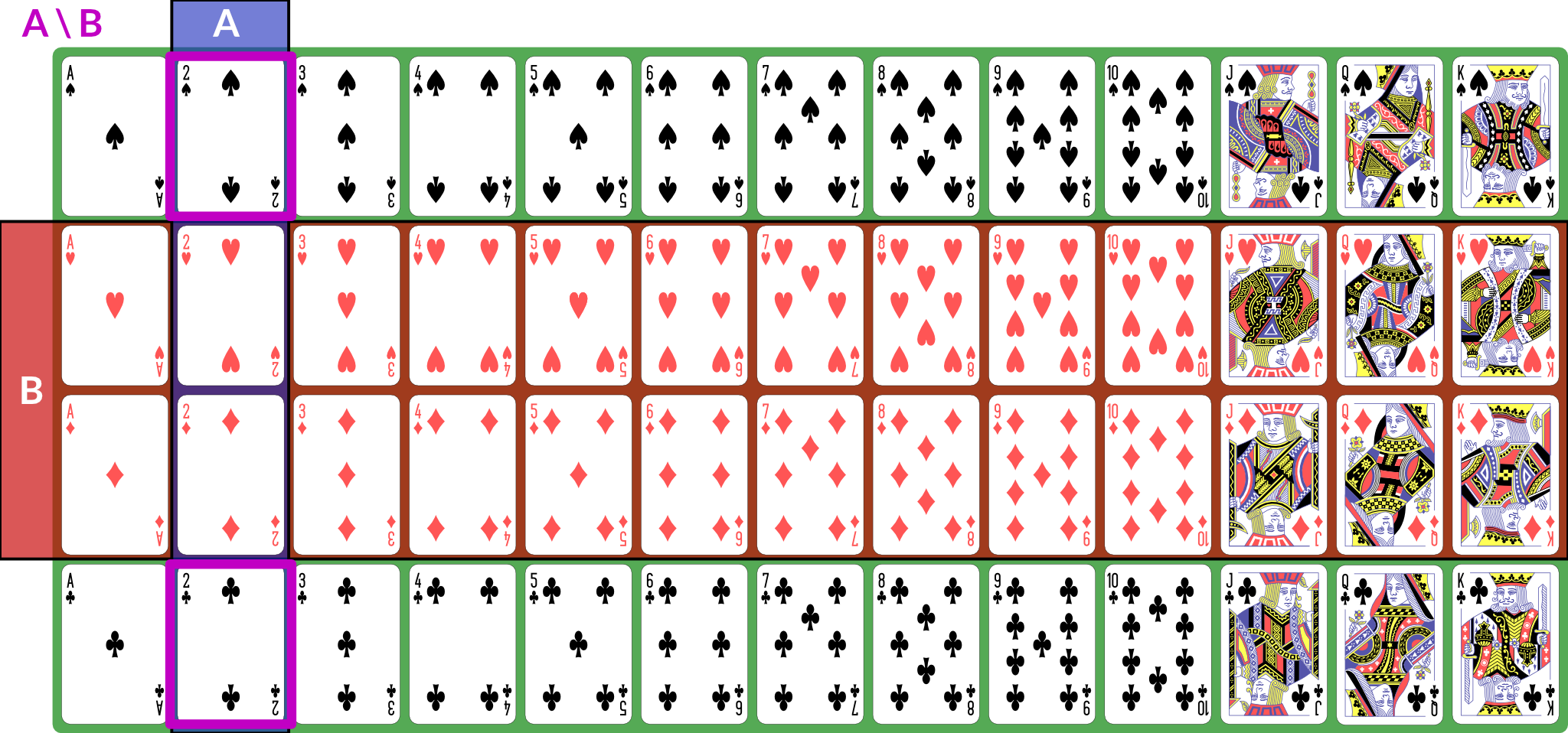

I also present the concepts here in 🧑🏻🏫 CS 533 Week 4. There are, broadly speaking, three kinds of sets in terms of their cardinality: We also talk about discrete and continuous sets: All finite sets are discrete. The natural numbers and integers are also discrete. The real numbers are continuous. Rationals and algebraics are also continuous, but we won’t be using them directly. A random process (or a process modeled as random) produces distinct individual outcomes, called elementary events. We use to denote the set of such outcomes; for a coin flip, . For a random process that produces a count, . Probability is defined over events. An event is a subset of (). If elementary events are events, they are represented as singletons: means “coin is heads”. , the set of all elementary events, is the event “something happened”. We use set operations to combine events (for these examples, we consider to be a deck of 52 standard playing cards; is “2” and is “red card”): is the event “both and happened”; for our example, the conjunction is “red 2”, of which there are 2 (2♥, 2♦). Illustration of is the event “either or (or both) happened”; for our example, the disjunction is “2 or red” — any 2, or any red card; this set has size 28: the 26 red cards (13 of each red suit), plus the two black 2s. Illustration of is the event “ happened but not ”. If , then ; for our example, the difference is “black 2”, because it is the set of 2s that are not red. Illustration of With these definitions, we can now define the event space: is the set of all possible events (subsets of ). This is a set of sets. It does not necessarily contain every subset of , but it has the following properties: is called a sigma algebra (or sigma field). For a finite set , we usually use , the power set of . This means that every possible subset of (and therefore every conceivable set of elementary events) is an event. Here are some additional properties of sigma algebras (these are listed separately from the previous properties because those are the definition of a sigma algebra and these are consequences — we can prove them from the definitions and axioms): Now that we have a sigma algebra, we can define the concept of probability. A probability distribution (or probability measure) over a sigma algebra is a function that obeys the following (Kolmogorov’s axioms): A collection of disjoint sets is also called mutually exclusive. What it means is that for any in the collection, — the two events cannot both happen simultaneously. We call a field of events equipped with a probability measure a probability space. What this probability measure does is that it describes how “much” of the total probability is associated with event. This is sometimes called the probability mass, because probability acts like a conserved quantity (like mass or energy in physics). There is a total probability of 1 (from the first axiom ); the probability measure over other events tells us how likely they are relative to other events by quantifying how much of the probability mass is placed on them: if , that tells us that half the probability mass is on event . This then has a variety of interpretations: The non-negativity axiom keeps us from trying to assign negative probabilities to events because they won’t be meaningful, and the countable additivity axiom ensures that probabilities “make sense” in a way consistent with describing a distribution of mass across the various events. If we have two distinct, disjoint events, then the probability mass assigned to the pair is the sum of their individual masses; the axiom generalizes this to countable sets of disjoint events. Some additional facts about probability that can be derived from the above axioms: We define the joint probability : the probability of both and happening in the same observation. This is sometimes also written , and commas and semicolons are sometimes mixed. This is usually to separate different kinds of events in the probability statement. The conditional probability , read “the probability of given ”, is the probability of conditioned on the knowledge that has happened. Conditional and joint probabilities decompose as follows: From this we can derive Bayes’ theorem: Bayes’ theorem gives us a tool to invert a conditional probability: given and the associated unconditional probabilities and , we can obtain . Crucially, this inversion requires the base rates, as expressed by unconditional probabilities, of and — the conditional probability alone does not provide sufficient information. In many interesting settings, such as Bayesian inference, we are looking to compute and compare for several different and the same . For such computations, we do not actually need unless we need the actual probabilities; if we simply wish to know which is the most likely for a given , we treat as fixed and look for the largest joint probability (sometimes called an unscaled probability, because we have not scaled it by to obtain a proper conditional probability). For such computations, we say that ( is proportional to ). Finally, we can marginalize a joint distribution by summing. If is a collection of mutually exclusive events that span , then: We call a partition of . By “span ”, we mean that for any , there is some such that . Two events are independent if knowing the outcome of one tells you nothing about the probability of the other. The following are true if and only if and are independent: If is continuous (typically ), then we can’t meaningfully talk about the probabilities of elementary events. The probability that an observation is exactly any particular value is (typically) zero. Instead, we define a sigma field where events are intervals: This is not the only way to define probabilities over continuous event spaces, but it is the common way of defining probabilities over real values. This particular sigma-field is called the Borel sigma algebra, and we will denote it . We often talk about continuous distributions as the distribution of a random variable . A random variable is a variable that takes on random values. We can (often) observe or sample a random variable. We define continuous probabilities in terms of a distribution function : This is also called the cumultaive distribution function (CDF). We can use it to compute the probability for any interval: This probability is called the probability mass on a particular interval. Distributions are often defined by a probability density function such that Unlike probabilities or probability mass, densities can exceed 1. When you use We can also talk about joint and conditional continuous probabilities and densities. When marginalizing a continuous probability density, we replace the sum with an integral: The expected value of a random variable , , is its mean. It is computed as the weighted sum over the possible values of , where the weight for each value is its probability (or density). For discrete with probability measure , we have: If is continuous and has probability density , we have: We can also talk about the conditional expectation , the expected value of given that we know event happened. It is defined as . The variance of a random variable is the expected value of its squared deviation from its mean: The standard deviation is the square root of variance (). The covariance of two random variables is the expected value of the product of their deviations from mean: The correlation . We can also show that . Random variables can also be described as independent in the same way as events: knowing one tells you nothing about the other. If two random variables are independent then their covariance (this implication is one-directional — there exist non-independent random variables whose covariance is 0). Expected value obeys a number of useful properties ( and are random variables, and , , etc. are real numbers): Sets can be described as an indicator function (or characteristic function) . This function is defined as: Then the expected value of this function is the same as the probability of : Another way of computing probability is to compute with odds: the ratio of probabilities for or against an event. This is given by: The log odds are often computationally convenient, and are the basis of logistic regression: The logit function converts probabilities to log-odds. We can also compute an odds ratio of two outcomes: So far, this document has focused on probability as a mathematical object: we have a probability space obeying a set of axioms, and we can do various things with it. We have not, however, discussed what a probability is. Is it a description of frequencies? Something else? Under the instrumentalist school of thought, the mathematical definition above is what a probability is. Probability is a measure over a sigma algebra that satisfies Kolmogorov’s axioms, nothing more, nothing less. In this view, all other interpretations of probability are simply applications of probability. Frequentism defines probability as the long-run behavior of infinite sequences: the probability of an event is the fraction of times it would appear if we repeated the experiment or observation infinitely many independent times. because, if we flip a coin infinitely many times, half of the results will be heads. Subjectivism or subjective Bayesianism defines probability as a consistent description of the beliefs of a rational agent. That is, it describes what the agent currently believes about as-yet-unobserved outcomes. because, prior to flipping a coin, the agent believes heads to be just as likely as tails. There are variants on these theories and other theories as well. They may seem similar, but they are very different in terms of their implications and application. For one thing, under frequentism, probabilities only make sense in the context of repeated (or theoretically repeatable) random events, and we cannot talk about the probability of a fixed but unknown thing, such as a population parameter. Under subjective Bayesianism, because probability is about the agent’s subjective state of belief, we can talk about the probability of a population parameter, because all we are doing is describing the agent’s belief about the parameter’s value. This thread by Michael Betancourt provides a good overview of the instrumentalist idea of probability, which treats probabilities simply as their mathematical objects. It influenced how I write about mass above. Some more tutorials from Jeremy Kun: If you want to dive more deeply into probability theory, Michael Betancourt’s case studies are rather mathematically dense but quite good: For a book:Set Concepts and Notation

Kinds of Sets

Events

Illustration

Probability

Joint and Conditional Probability

Independence

Continuous Probability & Random Variables

sns.distplot and it shows the kernel density estimator (KDE), it is showing you an estimate of the density. That is why the axis is weird.Expectation

Variance and Covariance

Properties of Expected Values

Expectation of Indicator Functions

Odds

Interpretation

Further Reading